Effectiveness of palliative home care on clinical, emotional and economic well-being at the end of life: a narrative review

Vincenza Giordano 1, Assunta Guillari 2, Aniello Lanzuise 3, Michele Virgolesi 2*,

Lidia Di Vaio 4 & Teresa Rea 2

- Department of General Surgery and Women's Health, A.O.R.N. (Hospital Company of National Significance) Antonio Cardarelli, Naples (Italy).

- Department of Public Health, University Federico II of Naples, Naples (Italy).

- Corporate Health Management, A.O.R.N. (Hospital Company of National Significance) Sant'Anna e San Sebastiano, Caserta (Italy).

- School of Medicine and Surgery, University Federico II of Naples, Naples (Italy).

* Corresponding author: Michele Virgolesi Ph.D., Department of Public Health, University Federico II of Naples, Sergio Pansini street no. 5, 80131, Naples (Italy). Email: michele.virgolesi@unina.it

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Palliative home care is essential for terminally ill patients. This integrated approach is not limited to physical care, but also embraces the psychological, social and spiritual aspects of the patient. This model of care, focused on the patient and their family, aims to ensure quality health care during the advanced stage of a disease. In addition, by reducing the need for hospital admissions, palliative home care reduces costs, providing a sustainable alternative for the health system.

Objective: To describe the knowledge related to the clinical, emotional and economic impact of palliative home care in cancer patients

Materials and Methods: A narrative review was conducted using databases such as PubMed, Cinahl and Cochrane Library between December 2023 and March 2024, using the Population, Intervention, Outcome (PIO) methodology. The survey generated 551 articles, of which only 6 were relevant to the study. The selection of studies was guided by inclusion and exclusion criteria, with a quality assessment using the Dixon Woods instrument.

Results: The studies included in the review have demonstrated a positive and significant impact of palliative home care on the well-being and quality of life of terminal cancer patients. Some of these studies have examined the clinical efficacy of such treatments in mitigating the patient's symptoms, with conflicting results: while some have shown positive efficacy, others have not found the same result. Regarding the cost-effectiveness, the analysis highlighted a lack of definitive evidence on the possible economic advantage of palliative home care compared to hospital care.

Conclusions: Palliative home care emerges as a crucial element in the nursing care of the terminally ill cancer patient: it offers essential psychological support, enabling patients to feel understood and listened to with regard to their needs and requirements. However, there are some discrepancies, particularly with regard to economic effects and symptom control.

Keywords: palliative home care; terminal care; quality of care; quality of life; cost-effectiveness analysis.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer represents one of the most significant global public health challenges of our time, with a significant and tangible impact on the lives of patients and their families [1,2]. Updated estimates by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), report almost 20 million new cancer cases worldwide (including non-melanoma skin cancers – NMSC) and 9.7 million cancer deaths (including NMSC). Data indicate that about one in five men or women develop cancer during their lifetime, while about one in nine men and one in 12 women die from it [3].

Over the years, the efforts of the scientific community have focused on improving the quality of life of cancer patients, who find themselves facing complex and challenging obstacles due to the disease. In this perspective, palliative care (PC), understood as the "active and holistic care of individuals of all ages with significant health-related suffering due to serious illness, and especially those nearing the end of life" [4] aims to improve the quality of life of patients, their families and caregivers. [5]

The typical patient undergoing palliative care for advanced cancer is often an older or elderly person with a diagnosis of metastatic or locally advanced malignancy, where curative options are limited or unavailable. This individual has probably been through numerous lines of cancer treatment, including surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, which over time have led to a progressive reduction in quality of life due to cumulative side effects and the disease itself [6]. The clinical condition is characterised by complex and multidimensional symptoms, such as chronic pain, dyspnoea, pronounced asthenia, cachexia, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and constipation. The patient may also manifest cognitive disorders or psycho-emotional symptoms, such as anxiety, depression and a sense of loss of autonomy, which reflect the heavy psychological impact of the terminal illness [7].

From the socio-familial point of view, the patient is often surrounded by a support network of close family members, but is confronted with the difficulty of having to accept the increasing dependence on others for activities of daily living. Often, this person is in ongoing dialogue with the palliative care team to manage symptoms and make shared decisions about end-of-life care while seeking to maintain some dignity and comfort in the remaining time [8].

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), PC represents one of the fundamental pillars of health care, involving more than 56.8 million people worldwide annually [9,10]. In Italy, about 1–1.4% of the population needs palliative care, recognised as an integral part of the human right to health [11,12]. In this context, palliative home care plays a crucial role. Palliative home care, in fact, is reflected in a model of care focused on the person, aimed at ensuring high-quality health care [5]. On the physical side, they alleviate debilitating symptoms associated with disease, such as pain, nausea and vomiting, reducing the cancer patient's physical suffering and improving his or her clinical well-being through pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies [13, 14]. On the emotional level, they offer complete psychological support to the patient and their family members, helping to meet their needs, in order to mitigate emotional distress and achieve spiritual balance [14-16]. This approach not only improves the quality of life of the terminally ill patient, but also alleviates the stress and anxiety of family members, creating a comfortable environment [17]. In the context of home care, nurses play a fundamental role in the delivery of palliative care, often representing the first point of contact for cancer patients. Growing evidence demonstrates the significant positive impact nurses have on the quality of care provided, improving symptom management, emotional support and overall coordination of care [18]. They are committed to creating a safe and efficient home environment, actively collaborating with the patient and family [18]. They instruct the latter on self-care techniques and the use of necessary medical equipment, promoting their autonomy [19]. They plan home care according to individual needs, constantly monitor the patient's clinical conditions and adapt interventions in a timely manner, acting promptly when necessary [19]. Finally, during the terminal stages of the disease, they provide support to the patient and caregivers, aimed at ensuring dignity and peace of mind, facilitating a respectful transition to death [12]. In addition, a study revealed that home care for cancer patients not only optimises their satisfaction, but also results in a more positive experience with a significant reduction in healthcare costs [20]. Patients receiving palliative home care are less likely to be hospitalised or go to the emergency room than those receiving standard care. This helps to reduce the frequency of hospital admissions, days spent in hospitals or care facilities, and medical services used, thus lowering the overall costs of end-of-life care [20-22]. It is estimated that care costs are reduced by about 34% in patients managed through PC compared to those who do not have access to PC.

In light of this, investigating the clinical, emotional and economic effectiveness of palliative home care appears to be of strategic importance in order to improve the approach to end-of-life care for cancer patients.

Objective

To describe the knowledge related to the clinical, emotional and economic impact of palliative home care in cancer patients

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A narrative review was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement (PRISMA) [23] and the guidelines for writing a narrative review to be published in peer-reviewed journals [24].

Study design

The research aims to answer the following question, formulated according to the Population, Intervention, Outcome (PIO) methodology: To what extent does palliative home care help to ensure clinically, emotionally and economically effective care for patients with terminal cancer over the age of 18?

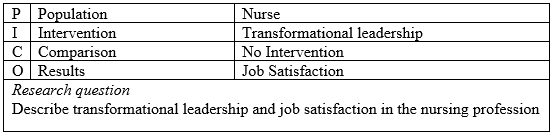

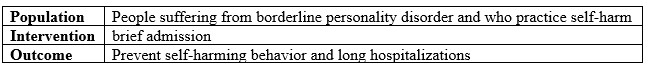

The PIO defines the population subject to analysis, the intervention to be implemented and the outcomes (Table 1).

| P | Patients > 18 years of age with terminal cancer |

| I | Palliative home care |

| O | Clinical, emotional and economic effectiveness |

Table 1. Question according to the PIO method.

Research strategy

Bibliographic research was conducted in the period between the end of December 2023 and March 2024, consulting the following scientific databases: PubMed, Cinahl, and the Cochrane Library. The keywords used for the research were: "palliative care", "palliative home care", "home care services", "home-based palliative care", "cancer", "cancer patients", "terminally ill", "terminal cancer", "quality of care", "quality of life", "cost-effectiveness analysis", "nurse-patient relations". The keywords were combined through the use of the Boolean operators "AND" and "OR", which made it possible to filter the results and make the search more specific.

Subsequently, to obtain general information on palliative care, websites of national bodies and scientific associations were consulted. These include the official websites of the Istituto Superiore della Sanità and the Ministry of Health, as well as those of associations such as the Italian Society of Palliative Care (SICP), the Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM), the Italian Association of Cancer Patients (AIMAC) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

During the first phase of research and the selection of studies, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined for the various databases, such as PubMed, Cinahl and the Cochrane Library. A restricted time criterion was applied, limiting the survey to articles published between 2019 and 2024. We included: a) primary studies; b) secondary studies; c) articles on patients with cancer over the age of 18; d) articles in English and Italian; e) articles available free of charge for the abstract and full text.

The following were excluded: a) studies concerning patients with oncological diseases under the age of 18 years and those concerning patients with non-oncological diseases; b) articles published before 2019 or which did not meet the stipulated time interval; c) articles written in a language other than English or Italian.

Selection of studies

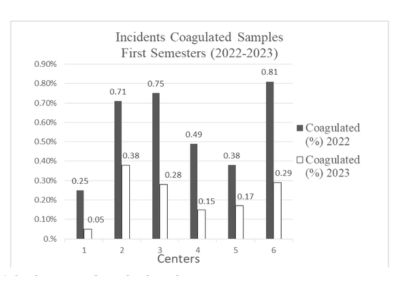

The survey yielded a total of 551 articles (389 on PubMed, 80 on Cinahl and 82 from the Cochrane Library).

The articles obtained from the three databases were analysed in the preliminary phase. 17 duplicate articles were excluded. The remaining 534 were examined by title and abstract. Of these, 485 were discarded because they were not relevant to the main theme or were inconsistent with the inclusion criteria. Of the 49 remaining articles, the full text was examined. Of these, 43 were excluded from the review because they were not suitable for the search objective and inclusion criteria when reading the full text; 6 articles were included.

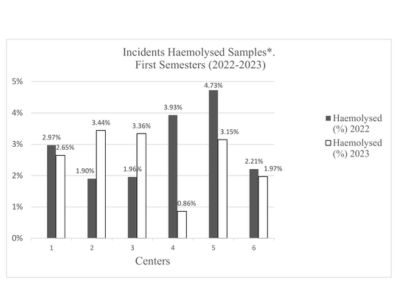

The method used in the selection of articles for this review is illustrated below in a flowchart compliant with the PRISMA-ScR (PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews) methodology [20]. This diagram highlights the final choice of the included articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart model of PRISMA-ScR (PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews).

Quality Assessment

To assess the methodological quality and homogeneity of the studies included in the review, the method proposed by Dixon-Woods was used by means of a specific checklist [25]. This checklist comprises five domains to assess the methodological quality of the studies, and each article was assigned an overall rating based on the assessment of these domains. Studies that received a score of less than 3 "yes" answers were excluded from the analysis. Those with 3 "yes" answers were considered discrete, while studies with 4 "yes" answers were classified as good and those with 5 "yes" answers were considered to be of excellent quality (Table 2).

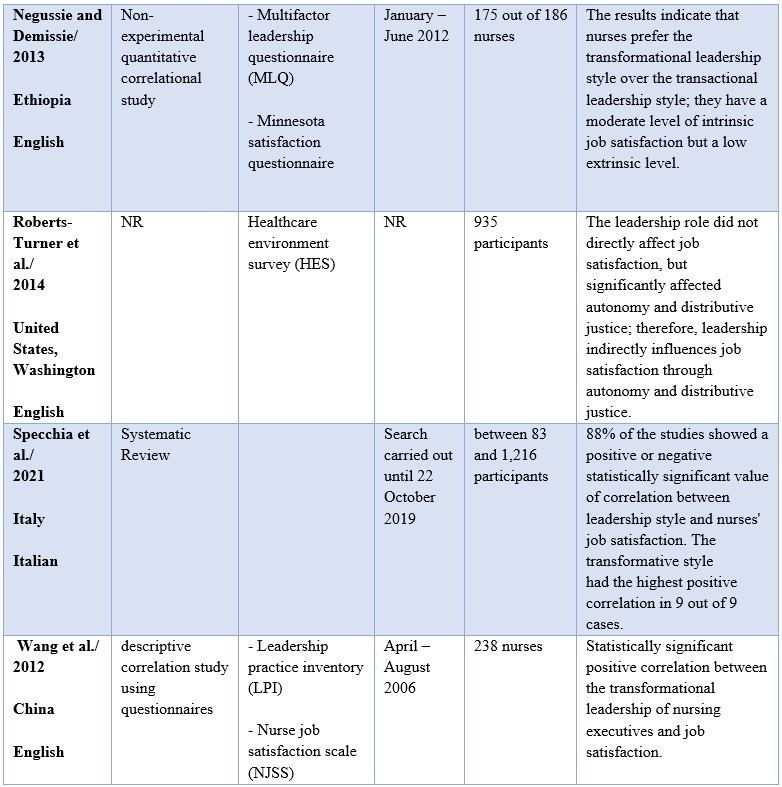

| Author(s), year | Are the aims and objectives of the research clearly stated? | Is the research design clearly specified and appropriate to the purposes and objectives of the research? | Do the researchers provide a clear account of the process by which their results were reproduced? | Do researchers present enough data to support their interpretations and conclusions? | Is the method of analysis appropriate and adequately explained? | SCORE |

| Patel et al., 2023 | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | Excellent |

| Riolfi al., 2021 | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | Excellent |

| Shepperd et al., 2021 | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | Excellent |

| Biswas al., 2022 | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | Good |

| Constantinou et al., 2022 | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | Excellent |

| Kim et al., 2022 | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | Excellent |

Table 2. Quality appraisal according to Dixon-Woods scale

RESULTS

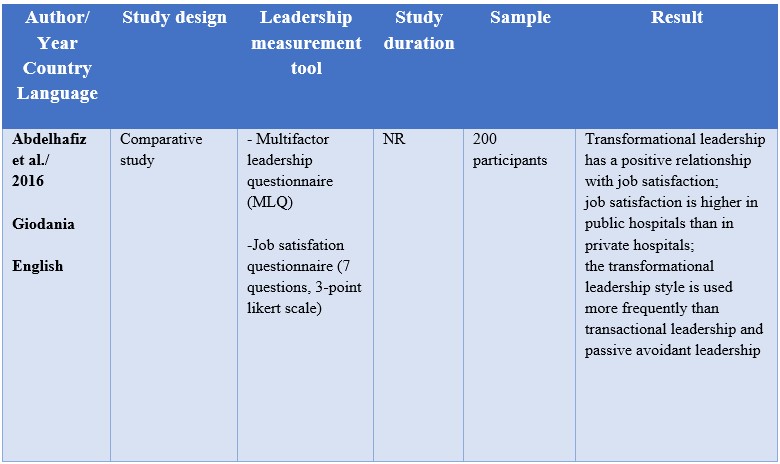

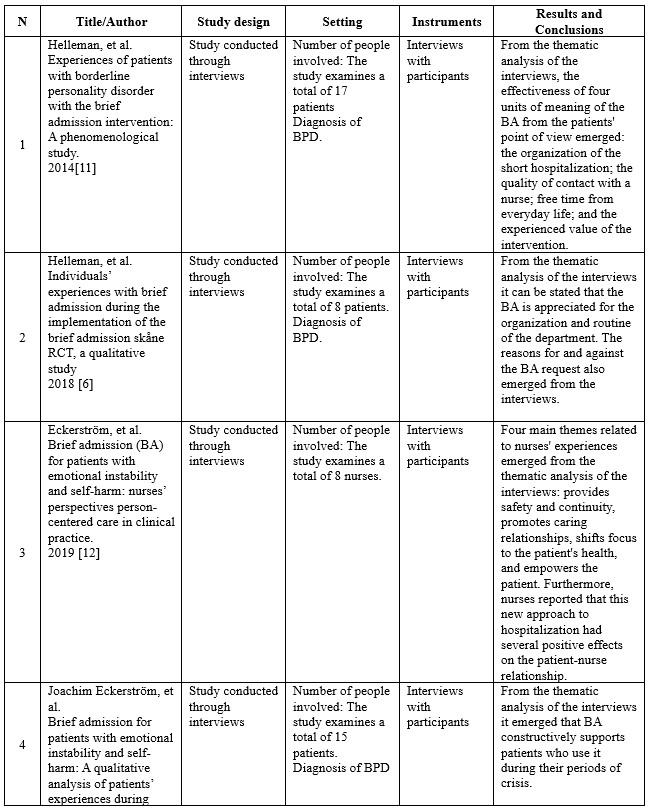

The results of the review highlighted six studies relevant to the research objective. These include two quantitative cross-sectional studies [26,27], a study using mixed methods [28], a retrospective study [29], a systematic review [30], and finally a cost-effectiveness study [31]. The studies were conducted in several countries, including Bangladesh [26], the Republic of Cyprus [27], India [28], Italy [29], the United Kingdom [30] and Korea [31]. The studies selected by the review involve a total of 1702 patients with cancer. 68 patients participated in the mixed study [28], 375 patients in the retrospective cohort study [29], 1128 patients in the systematic review [30], while 131 patients were involved in the remaining quantitative cross-sectional studies [26,27]. The cost-effectiveness analysis considered a hypothetical cohort of patients with terminal cancer [31]. In two studies [28,29], patients enrolled were predominantly male; in one observational study [26], by contrast, 76.5% of patients were female. Only in one study were there similar proportions between men and women [30]. Of the six included studies, the mixed method study compared palliative home care with hospice care [28], while two studies [30,31] compared palliative home care with the usual palliative care in inpatient units. The main characteristics of the studies are summarised in the following summary table (Table 3);

| Author, year | Study design | Population | Country in which the study was carried out | Goal of the study | Results |

| Biswas al., 2022 [26]

|

Cross-sectional study

|

n=51 terminal cancer patients | Bangladesh | Assessing the quality of life of patients with cancer illnesses receiving palliative home care. Identify the factors that influence physical well-being and symptom control. | Palliative home care proved effective in promoting social and emotional well-being for the majority of patients included in the study. However, it showed limited effectiveness in controlling symptoms. |

| Constantinou et al., 2022 [27]

|

Cross-sectional study

|

n=80 patients with cancer | Republic of Cyprus | Conducting an analysis of the quality and effectiveness of palliative care delivered at home, while assessing the level of patient satisfaction. | Participants rated the overall quality of palliative home care positively, highlighting a satisfactory level of psychological support. |

| Patel et al., 2023 [28] | Mixed method study | n=68 patients with terminal cancer | India | Examining how patients with terminal cancer perceive the quality of palliative care in different contexts and measuring quality of life.Inizio modulo | - Positive impact on the QoL of the terminal patient both at home and in the Hospice.

The need to expand access to palliative care, increasing its coverage. |

| Riolfi al., 2021 [29]

|

Retrospective cohort study |

n=375 cancer patients | Italy | Examining the effectiveness of palliative home care in reducing costs by minimising admissions to acute care facilities. | Palliative home care reduces hospital admissions and hospital days in the last two months of life, while increasing the probability of death at home, ensuring the patient's well-being at the end of life. |

| Shepperd et al., 2021 [30]

|

Systematic review

|

n=1128 patients in the terminal stage | United Kingdom | Examining the effectiveness of palliative home care in reducing the likelihood of death in the hospital setting, in mitigating patient symptoms, in reducing health system costs, as an alternative to hospital and hospice care | Palliative home care increases the likelihood of death at home for the patient. Uncertainty persists regarding symptom control and the impact on health system costs. |

| Kim et al., 2022 [31]

|

Cost-effectiveness analysis study

|

Hypothetical cohort of terminal cancer patients who have benefited from palliative home care. | Korea | To investigate the economic advantage of palliative home care compared to hospital care. | Palliative home care can result in a doubling of expenses compared to hospital care. However, the cost-benefit outcome is uncertain. |

Table 3. Summary of the selected studies

Clinical effectiveness

Two studies included in the review show a positive effectiveness of palliative home care in alleviating patients' symptoms [28,29], while others do not find the same result [26,30]. The study by Riolfi et al. [26] showed that patient care by palliative home care services improves the control of psycho-physical symptoms that occur towards the end of life. Similarly, Patel et al. [28] highlighted effective symptom management by the home care team. In contrast, the research by Biswas et al. [26] found below-average physical well-being in 60.8% of the patients included in the survey, who complained of feeling sick (54.9%), lack of energy (43.1%), and pain (47.1%). The study calls for more research aimed at improving interventions for symptoms. Finally, the study conducted by Shepperd et al. [30] shows uncertain outcomes on symptom control.

Emotional effectiveness

Three studies [26-28] have highlighted the positive impact of palliative home care on the well-being and quality of life of patients with cancer. In the study by Biswas et al. [26], 92.1% of patients who received palliative home care demonstrated above-average emotional and social well-being. However, the greater well-being seems to be related to the duration of the care provided (> months) and to a less ominous prognosis. The investigations by Constantinou et al. [27] and Patel et al. [28] also reveal that palliative home care guarantees greater psychological support.

Cost effectiveness

The impact of palliative home care on health system costs has been the subject of conflicting considerations among the various studies included in the review. The study conducted by Riolfi et al. [29] indicates potential savings thanks to palliative home care that reduces costs related to hospitalisation, access to the emergency room and days in hospital. In contrast, the systematic review conducted by Shepperd et al. [30] highlighted a certain degree of uncertainty regarding the effect of home services on health system costs. The study conducted by Kim et al. [31] also revealed ambiguous and inconclusive results.

DISCUSSION

This review provided an analysis of the clinical, emotional and economic effectiveness of home palliative care for terminal cancer patients. A positive and significant effect of such treatments on patients' psychological well-being was found, in line with studies conducted by Biswas et al. [26], Constantinou et al. [27] and Patel et al. [28]. Home care has been shown to offer essential psychological support, enabling patients to feel understood and listened to about their needs and alleviating the emotional burden of illness. The choice to die at home promotes the emotional well-being of terminal patients, maintaining normality and social integration until the end of life [29-31]. Family support offers spiritual and emotional comfort, reducing anxiety and discomfort. Indeed, none of the research conducted showed that patients prefer to die in a hospital environment rather than in their home environment. However, only a fraction of the estimated total of patients who require it manage to benefit from it. A 2019 study, based on data collected through the palliative home care monitoring portal, showed that in 2013, 38,384 cancer patients were assisted by home care units [32], while many others could not benefit from such services. The Italian reality, therefore, does not guarantee uniform coverage throughout the country; suffice it to say that, at present, only 59% of the local health authorities have an active palliative care network, highlighting the urgent need to expand access [29,33]. The lack of studies conducted specifically in Italy is also a significant limitation in understanding the clinical, emotional and economic effectiveness of home palliative care in the terminal cancer patient. In fact, only one study [29] considered this scenario, whereas the other surveys included in the review refer to different countries. It is well known that differences in health care systems, available resources and modes of care between countries can greatly influence the results of studies and complicate the extension of results in a different context.

One study suggests potential cost savings through home-based services [29], while others, such as the research by Shepperd et al. [30] and Kim et al. [31], point to uncertainties or a lack of significant differences in costs compared to hospital care. It is not yet clear whether home care is more beneficial in terms of results and costs for terminal cancer patients. This highlights the need for further research on the economic impact of palliative home care. Although the cost-effectiveness analysis is not conclusive, the lack of negative impacts on other results could justify the implementation of home services to meet the needs of patients.

Similarly, with regard to symptom control, a diversity in results has emerged that highlights the importance of adopting personalised approaches to manage them effectively.

Palliative home care brings emotional benefits, but uncertainties remain regarding its effectiveness in controlling symptoms and its economic impact compared to hospital care. It is essential to consider patient diversity when designing personalised strategies. Further detailed research is needed to examine these aspects. Despite this, the implementation of home care programmes for end of life seems promising, but it is essential to improve and expand services to respond to the growing demand and ensure adequate support for patients in their home environment.

In this context, the nurse assumes a vital role in offering complete and patient-centred care, designing a personalised care plan. Through specialised training and constant professional updating, the nurse is able to guarantee high-quality palliative care, working in close collaboration with the other professionals in the palliative care team. This multidisciplinary approach ensures that the physical, emotional and spiritual needs of the patient are adequately met [34]. Using their skills, the nurse educates the patient on the management of typical symptoms that can occur during the terminal phase of cancer, such as pain, nausea and dyspnoea, teaching the patient strategies that can be effective.

Nursing not only allows the patient to autonomously manage symptoms, but also helps to provide a feeling of security and tranquillity regarding their situation [35].

At the same time, the nurse is actively engaged in the education of family members, so that they can acquire the skills and competences necessary to offer the appropriate support to the patient [36,37]. In addition, the nurse provides information on the resources available in the community, such as support groups, to expand the usable support network, in order to support the patient and their family during the course of the disease. This significantly contributes to preventing the patient and their loved ones from feeling isolated during this delicate phase [38]. However, nursing care is not only limited to alleviating physical suffering; in fact, the role of the nurse at this critical moment is crucial and goes far beyond the simple monitoring of physical symptoms. They offer constant and comprehensive support to both the patient and their family members, improving quality of life until the last moment. The main objective is to face the evolution of the disease in the most comfortable, reassuring and respectful way possible, and to facilitate a smooth transition towards the end of life that allows the patient to manage their condition with dignity and peace of mind [10,28,33].

Limitations of the study

This review has some limitations, which hinder its applicability in the context of the Italian health system. First, the limited number of databases consulted may have reduced the amount of articles identified, potentially excluding relevant information. The choice of inclusion criteria, although targeted, excluded studies relating to palliative care delivered at the outpatient and hospice level, focusing exclusively on home care. This approach, while guaranteeing a precise focus, on the other hand limits the completeness of the data collected and loses useful knowledge, excluding a broader vision of palliative care.

Some of the studies included in the review [26-28] had unrepresentative or small samples of participants, which could influence the generalisability of the results.

Implications for clinical practice

The review suggests that palliative home care may be useful for patients with terminal cancer. In particular, the review highlights the benefits that could be derived from the use of palliative home care in promoting the psychological well-being of cancer patients and enabling terminal patients to spend their last days in the comfort of their own home environment, as desired by them. In fact, in order to apply the results of the review, it is essential to implement palliative home care programmes and services that reduce the use of hospital facilities. Adequate human resources must be provided, suitably trained in palliative home care. The health personnel involved in the treatment, in fact, must have advanced skills in pain management, symptom control and coordination of health and social services. This approach not only aims to improve the quality of life of the patient through a more effective control of symptoms, but also to offer fundamental emotional and social support during the advanced stages of a disease. The continuity of home care allows to establish relationships of trust between the patient, family members and the medical team, facilitating a more personalised and human-centred management of care.

Another crucial point concerns the careful monitoring of symptoms. Implementing specific protocols for the assessment and management of symptoms allows treatment to be adapted in a timely manner to the individual needs of the patient, ensuring optimal comfort and improving quality of life even in the most delicate phases. However, it is also essential to consider the economic aspect of palliative home care, therefore, studies dealing with the continuous and accurate cost-benefit assessment are required to balance the clinical effectiveness with the economic sustainability of such interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

The objective of the study was to describe the knowledge related to the clinical, emotional and economic impact of palliative home care in cancer patients. The review conducted suggests that palliative home care is a crucial element in the care of the terminally ill cancer patient, fundamental to ensuring adequate end-of-life management.

Our review shows that home care offers essential psychological support, enabling patients to feel understood and listened to with regard to their needs and requirements. However, some discrepancies have emerged, particularly with regard to the effectiveness of PC in terms of symptom control and reduction of economic costs, therefore, it is hoped that more field studies will be carried out in order to provide a broader and more detailed picture of the effectiveness of palliative care in these areas.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research received no external funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

All authors contributed equally.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer. Last access: 29 February, 2024.

- The Italian Ministry of Health. Piano Oncologico Nazionale: documento di pianificazione e indirizzo per la prevenzione e il contrasto del cancro 2023-2027 ("National Cancer Plan: planning and guidance document for cancer prevention and control 2023-2027"), p. 7-8. Available at: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_3291_allegato.pdf. Last access: 29 February, 2024.

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 May–Jun;74(3):229-263. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21834.

- Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, Wenk R, Ali Z, Bhatnaghar S, Blanchard C, Bruera E, Buitrago R, Burla C, Callaway M, Munyoro EC, Centeno C, Cleary J, Connor S, Davaasuren O, Downing J, Foley K, Goh C, Gomez-Garcia W, Harding R, Khan QT, Larkin P, Leng M, Luyirika E, Marston J, Moine S, Osman H, Pettus K, Puchalski C, Rajagopal MR, Spence D, Spruijt O, Venkateswaran C, Wee B, Woodruff R, Yong J, Pastrana T. Redefining Palliative Care-A New Consensus-Based Definition. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Oct;60(4):754-764. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027.

- Heydari H, Hojjat-Assari S, Almasian M, Pirjani P. Exploring health care providers' perceptions about home-based palliative care in terminally ill cancer patients. BMC Palliative Care. 2019;18(1):66. DOI: 0.1186/s12904-019-0452-3

- Temel, J.S., et al. "Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer." New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 363, no. 8, 2010, pp. 733-742. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678.

- Ferrell, B. R., et al. "Palliative care in chronic illness and cancer: A narrative review." Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 172, no. 5, 2020, pp. 350-356. DOI: 10.7326/M19-3085.

- Kamal, A. H., et al. "Symptom prevalence, treatment patterns, and outcomes among patients with advanced cancer: A National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey analysis." JAMA Oncology, vol. 3, no. 5, 2017, pp. 672-678. DOI: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6746.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Palliative care 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care. Last access: 14 February, 2024.

- Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance (WHPCA) and World Health Organization (WHO). Global Atlas of Palliative Care 2nd Edition. London, 2020. Available at: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/integrated-health-services-(ihs)/csy/palliative-care/whpca_global_atlas_p5_digital_final.pdf?sfvrsn=1b54423a_3. Last access: 14 February, 2024.

- The Italian Society of Palliative Care (SICP). Palliative care & IFeC. 2023. Available at: https://www.sicp.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/FNOPI-SICP_CP-e-IFEc_V2-Apr23.pdf. Last access: 4 March, 2024.

- The Italian Ministry of Health. Cure palliative in ospedale: un diritto di tutti 2021. ("Palliative care in the hospital: a right for everyone 2021")Available at: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_opuscoliPoster_518_allegato.pdf. Last access: 29 February, 2024.

- Qanungo S, Cartmell KB, Mueller M, Butcher M, Sarkar S, Carlson TG, et al. Comparison of home-based palliative care delivered by community health workers versus usual care: research protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Palliative Care. 2023;22(1). DOI: 10.1186/s12904-023-01235-z

- Maetens A, Beernaert K, De Schreye R, Faes K, Annemans L, Pardon K, et al. Impact of palliative home care support on the quality and costs of care at the end of life: a population-level matched cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e025180. DOI: 1136/bmjopen-2018-025180

- Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative Care: the World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(2):91-6. DOI: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00440-2.

- Dhiliwal SR, Ghoshal A, Dighe MP, Damani A, Deodhar J, Chandorkar S, et al. Development of a model of Home-based Cancer Palliative Care Services in Mumbai - Analysis of Real-world Research Data over 5 Years. Indian J Palliative Care. 2022;28(4):360-390. DOI: 25259/IJPC_28_2021

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of palliative home care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(6) DOI: 1590/1516-3180.20161341T2

- Van Klinken M. Palliative and End-of-Life Care: Challenges for Patients and Nurses. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2023;39(6):151527. DOI: 1016/j.soncn.2023.151527

- Danielsen BV, Sand AM, Rosland JH, Førland O. Experiences and challenges of home care nurses and general practitioners in home-based palliative care - a qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care. 2018;17(1):95. DOI: 1186/s12904-018-0350-0

- Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, Seitz R, Morgenstern N, Saito S, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):993-1000. DOI: 1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x

- Gonzalez-Jaramillo V, Fuhrer V, Gonzalez-Jaramillo N, Kopp-Heim D, Eychmüller S, Maessen M. Impact of home-based palliative care on health care costs and hospital use: A systematic review. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2021;19(4):474-487. DOI: 1017/S1478951520001315

- Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(5):715-24. DOI: 1089/109662103322515220

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-473. DOI: 7326/M18-0850

- Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5(3):101-17. DOI: 1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

- Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1). DOI: 1186/1471-2288-6-35

- Biswas J, Faruque M, Banik PC, Ahmad N, Mashreky SR. Quality of life of the cancer patients receiving home-based palliative care in Dhaka city of Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2022;17(7). DOI: 1371/journal.pone.0268578

- Constantinou A, Polychronis G, Argyriadi A, Argyriadis A. Evaluation of the quality of palliative home care for cancer patients in Cyprus: a cross-sectional study. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2022;27(9):454-62. DOI: 12968/bjcn.2022.27.9.454

- Patel D, Patel P, Ramani M, Makadia K. Exploring Perception of Terminally Ill Cancer Patients about the Quality of Life in Hospice based and Home-based Palliative Care: A Mixed Method Study. Indian J Palliative Care. 2023;29(1):57-63. DOI: 25259/IJPC_92_2021

- Riolfi M, Mogliani E, Salvetti I, Poles G, Trivellato E, Manno P. Efficacy and criticality in palliative home care for cancer patients: retrospective cohort study. Recent Prog Med 2021;112(10):647-652. DOI: 10.1701/3679.36655

- Shepperd S, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Straus SE, Wee B. Hospital at home: home-based end-of-life care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;3(3). DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009231

- Kim YS, Han E, Lee JW, Kang HT. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of HomeBased Hospice-Palliative Care for Terminal Cancer Patients. J Hosp Palliative Care. 2022;25(2):76-84. DOI: 14475/jhpc.2022.25.2.76

- Scaccabarozzi G, Lovaglio PG, Limonta F, Peruselli C, Bellentani M, Crippa M. Monitoring the Italian Home Palliative Care Services. Healthcare (Basel). 2019 Jan 2;7(1):4. DOI: 3390/healthcare7010004

- The Italian Society of Palliative Care (SICP). Le cure palliative in Italia: stima del bisogno, rete di offerta, tasso di copertura del bisogno, confronto internazionale. ("Palliative care in Italy: estimation of need, supply network, need coverage rate, international comparison.") 2020. Available at: https://www.sicp.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Cure-palliative-in-talia_Bocconi_211119.pdf. Last access: 31 May, 2024.

- Law no. 38 of 15 March 2010, art. 1 – "Disposizioni per garantire l'accesso alle cure palliative e alla terapia del dolore" ("Provisions to guarantee access to palliative care and pain therapy") (OJ no. 65 of 19/03/2010). Available at: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it. Last access: 10 February, 2024.

- Marchetti A, Piredda M, Facchinetti G, Virgolesi M, Garrino L, Dimonte V, De Marinis MG. Nurses' Experience of Body Nursing Care: A Qualitative Study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2019 Mar/Apr;33(2):80-89. DOI: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000314.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Therapeutic patient education: an introductory guide. 2023. Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/372743/9789289060219-eng.pdf?sequence=12. Last access: 6 March, 2024.

- Collins CM, Small SP. The nurse practitioner role is ideally suited for palliative care practice: A qualitative descriptive study. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2019; 29(1):4-9. DOI: 5737/2368807629149

- Hassankhani H, Dehghannezhad J, Rahmani A, Ghafourifard M, Soheili A, Lotfi M. Caring Needs of Cancer Patients from the Perspective of Home Care Nurses: A Qualitative Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022; 23(1):71-77. DOI: 31557/APJCP.2022.23.1.71

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

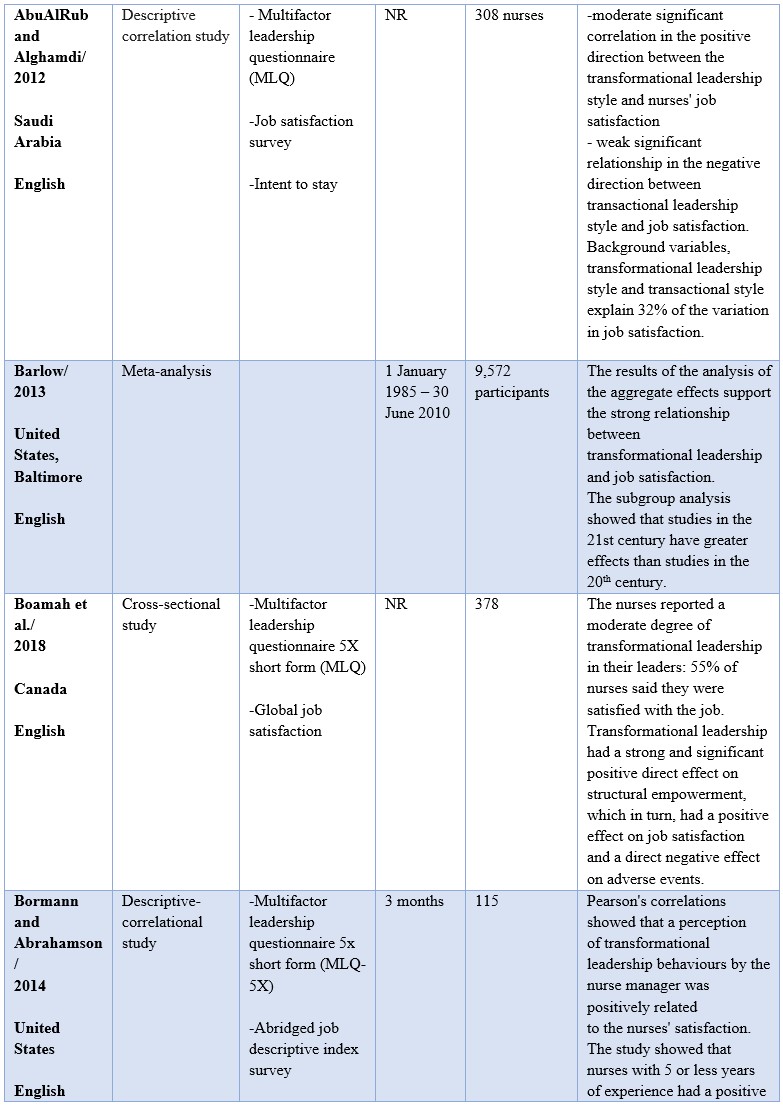

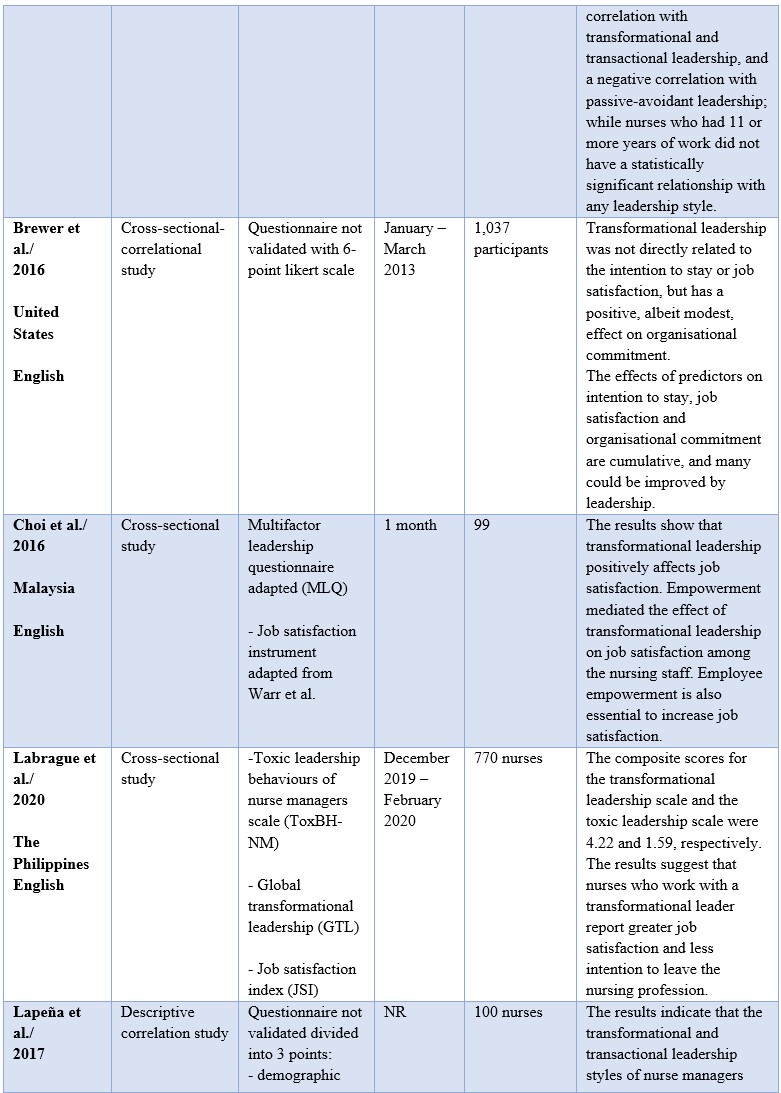

Transformational Leadership: the key to reducing Intention to Leave In nurses

Gianluca Azzellino 1*, Massimo Bordoni2

- Department of Territorial Assistance, Local Health Authority (AUSL 04) of Teramo, Italy

- Department of Social Health. Local Health Authority (AUSL 04) of Teramo, Italy

Corresponding author: Gianluca Azzellino, Department of Social Health. Local Health Authority (AUSL 04) of Teramo, Via Finlandia n. 7/1,65015 Montesilvano, Italy Email: gianluca.azzellino@aslteramo.it

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

This commentary responds to the recently published article on transformational leadership in the healthcare context. The article explores how transformational leadership can significantly improve efficiency and job satisfaction in nursing teams. Specifically, it highlights the crucial role of this leadership style in fostering a positive work environment and reducing intentions to leave the profession among nurses. At a time of profound crisis for the nursing profession, characterised by staff shortages, increased workload and high rates of abandonment of the profession, transformational leadership could represent an effective model to address these challenges. This leadership approach, based on vision, inspiration, and involvement, can strengthen nurses' motivation and satisfaction by promoting a positive and stimulating working environment. The analysis emphasises the importance of adopting innovative management practices to address current challenges in the healthcare sector, providing a basis for further research and practical implementation.

Keywords: Nursing leadership, Burnout, intention to leave, professional development, nurse education, job satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

The authors read with interest the article by Rizzo et al. (2024) entitled “Transformative leadership and job satisfaction in the nursing profession: A narrative review”. The article offers an in-depth analysis of the effect of transformative leadership on the nursing profession. The authors explore how this leadership style not only positively influences nurses’ job satisfaction, but also their intention to leave the profession. This is particularly relevant in a global context in which the nursing shortage is a critical challenge for healthcare systems. However, the increasing complexity of the healthcare system, coupled with the new challenges posed by the global pandemic, has made the need for an evolution in the nursing leadership model evident. This commentary aims to further explore the findings of Rizzo et al. by contextualizing their study within the current issues facing the nursing profession and discussing the importance of implementing transformative leadership strategies to improve both the quality of healthcare and the intention to stay. Our analysis through a combination of direct experience in the field and critical review of relevant literature, proposes to offer an in-depth perspective on how transformational leadership can be implemented effectively to address current challenges in nursing.

DISCUSSION

It was interesting to read the research work by Rizzo et al. (2024) on the relationship between transformational leadership and job satisfaction. At a time when the healthcare sector is facing unprecedented challenges, stability and satisfaction of nurses have become crucial priorities. Transformational nurse leaders can recognise and anticipate the needs of their nursing staff by establishing a good rapport and making significant efforts to meet their needs to encourage a sense of empowerment and autonomy that can subsequently translate into job satisfaction [1]. Recent studies have shown that nurses working under the guidance of transformational leaders tend to show greater attachment to their role and to the organisation. This results in fewer people leaving the profession, thus reducing turnover and the costs associated with training and induction of new staff. Transformational leadership, defined by Bass as a leadership style that inspires and motivates employees through shared vision, effective communication, individualised attention, and intellectual stimulation, stands out as a leadership model capable of fostering a positive and motivating work environment [2]. A leadership style that promotes autonomy, support and empowerment of nurses can improve job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and nurses' intention to remain in their position by reducing emotional exhaustion [3]. As Rizzo et al. points out, there is therefore a need to identify and fill current gaps in nursing leader competencies and skills through processes of two-way communication and mutual trust between managers and nurses. Cummings et al. conducted a systematic review that showed that transformational leadership behaviour is positively correlated with job satisfaction [4]. Strengthening the sense of belonging and personal fulfilment can reduce burnout and the intention to leave the profession. In an environment where nurses feel valued and supported, they are more likely to remain committed and motivated in their work. Overall, studies support the fact that having positive support factors and working relationships in place, including positive relationships with physicians, leader support, positive leadership style and teamwork, can play a protective role against Burnout [5]. Another positive aspect of this style is its ability to motivate professionals to overcome daily challenges and actively engage in their work. Leaders who display transformational behaviour can inspire staff to see their work as a meaningful mission, rather than just an occupation. Kanste highlighted how transformational leaders are able to foster a sense of purpose among nurses, encouraging them to contribute beyond basic expectations [6]. This increased motivation can result in a reduction in the intention to leave the profession. A cohesive environment can improve the quality of care and increase job satisfaction. Boamah et al. showed how transformational leadership fosters the creation of cohesive and collaborative teams, thus improving outcomes for both patients and nurses. This team cohesion can reduce feelings of isolation and increase the sense of support among staff [7]. Professional development programmes that focus on transformational leadership skills can prepare nurse leaders to lead their teams effectively. It is therefore crucial to invest in the training of leaders capable of adopting this leadership style in order to build motivated and resilient teams. Despite the fact that a transformational leadership style is correlated with better job satisfaction, existing evidence shows that it is rarely used by nursing leaders in healthcare settings [8]. Furthermore, fostering a culture of continuous feedback and professional growth can help leaders develop and maintain transformational behaviours. Secondly, it is crucial to promote policies that foster work-life balance, the creation of open and transparent communication channels, and the recognition and valuing of nurses' contributions. The choice of the best leadership style could be one of the modifiable factors that a healthcare organisation can adopt to create a favourable working environment and promote quality care [9]. Rizzo et al. correctly identified the increasing pressures on nurses and the need for innovative strategies to address the problem. However, we believe that an emphasis on transformational leadership can offer a sustainable solution and practice. The scientific community and policy makers need to seriously consider adopting this leadership model as part of strategies to address the professional crisis. Transformational leadership offers a promising perspective to improve job satisfaction, reduce burnout and intent to leave, and thus contribute to building a more attractive and sustainable healthcare system.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests

Financing

No funding to declare

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the work

REFERENCES

- Asif M, Jameel A, Hussain A, Hwang J, Sahito N. Linking Transformational Leadership with Nurse-Assessed Adverse Patient Outcomes, and the Quality of Care: Assessing the Role of Job Satisfaction and Structural Empowerment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Jul 4;16(13):2381. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132381. PMID: 31277478; PMCID: PMC6651060.

- Jr, Morgan. (2006). Leadership and performance beyond expectations, by Bernard M. Bass. New York: The Free Press, 1985, 191 pp. $26.50. Human Resource Management. 25. 481 - 484. 10.1002/hrm.3930250310.

- Laschinger HK, Wong CA, Cummings GG, Grau AL. Resonant leadership and workplace empowerment: the value of positive organizational cultures in reducing workplace incivility. Nurs Econ. 2014 Jan-Feb;32(1):5- 15, 44; quiz 16. PMID: 24689153.

- Cummings GG, Tate K, Lee S, Wong CA, Paananen T, Micaroni SPM, Chatterjee GE. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018 Sep;85:19-60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.04.016. Epub 2018 May 3. PMID: 29807190.

- Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Reinius M, Griffiths P. Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review. Hum Resour Health. 2020 Jun 5;18(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00469-9. PMID: 32503559; PMCID: PMC7273381.

- Kanste, Outi. (2008). The Association between Leadership Behaviour and Burnout among Nursing Personnel in Health Care. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research. 28. 4-8. 10.1177/010740830802800302.

- Boamah SA, Spence Laschinger HK, Wong C, Clarke S. Effect of transformational leadership on job satisfaction and patient safety outcomes. Nurs Outlook. 2018 Mar-Apr;66(2):180-189. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.10.004. Epub 2017 Nov 23. PMID: 29174629.

- Morsiani G, Bagnasco A, Sasso L. How staff nurses perceive the impact of nurse managers' leadership style in terms of job satisfaction: a mixed method study. J Nurs Manag. 2017 Mar;25(2):119-128. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12448. Epub 2016 Dec 5. PMID: 27917561.

- Phillips LA, de Los Santos N, Jackson J. Licensed practical nurses' perceptions of their work environments and their intentions to stay: A cross-sectional study of four practice settings. Nurs Open. 2021 Nov;8(6):3299-3305. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1046. Epub 2021 Aug 25. PMID: 34432374; PMCID: PMC8510757.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Monitoring of toxicities induced by Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell therapy: Protocol for a phenomenological study on the experiences of nurses

Valentina Simonetti 1†, Letizia Governatori 2†, Francesco Galli 3, Cesare Tozzi 4, Romano Natalini 4,

Andrea Toccaceli 5, Francesco Pastore 6, Giancarlo Cicolini 1 & Dania Comparcini 7*

- Department of Innovative Technologies in Medicine and Dentistry, “G. d 'Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy; v.simonetti@unich.it; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7185-4850 (VS); g.cicolini@unich.it; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2736-1792 (GC).

- Department of General and Specialist Surgery, Adult and Pediatric Orthopaedics Clinic, University Hospital "Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Delle Marche", Ancona, Italy; letizia.governatori@ospedaliriuniti.marche.it (LG).

- Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, Polytechnic University of Marche, Ancona, Italy; galli.francesco77@gmail.com; https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3550-1268 (FG).

- Department of Internal Medicine, Haematology Clinic, PICC Unit, University Hospital "Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Delle Marche", Ancona, Italy; tozzicesare1973@gmail.com (CT); romano.natalini@ospedaliriuniti.marche.it. (RN).

- Nursing Department, University Hospital "Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Delle Marche", Ancona, Italy; andrea.toccaceli@ospedaliriuniti.marche.it (AT).

- Department of Biomedicine and Prevention, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy; francesco.pastore@uniba.it (FP).

- Interdisciplinary Department of Medicine, “Aldo Moro” University of Bari, Bari, Italy; dania.comparcini@uniba.it; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3622-6370 (DC).

† The authors LG and VS contributed to the study in equal measure.

* Corresponding author: Dania COMPARCINI (DC), PhD, MSc, RN, research fellow. Interdisciplinary Department of Medicine, “Aldo Moro” University of Bari, Italy; email: dania.comparcini@uniba.it; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3622-6370.

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T) represents the most recent immunotherapy’s innovation to cure some refractory and/or relapsing haematological tumours.

However, because of the life-threatening toxicities it might cause such as Cytokine Release Syndrome and Immune Cell Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome, patients are closely monitored by nurses for the early identification of toxicities during the post-infusion phase of CAR-T cell therapy. Exploring the nurses’ experience with respect to any difficulties related to the monitoring is important since these issues can be perceived by patients and affect the nurse-patient’s caring relationship, considered as a shared lived experience between the patient and the nurse.

Aim: This study aims to investigate haematology nurses’ lived experience with monitoring CAR-T’s induced toxicities.

Materials and methods: A qualitative study following Cohen's phenomenological methodology will be conducted through semi-structured interviews in a sample of Italian nurses working in haematology units, who have had previous experience in the management of patients undergoing CAR-T therapy for at least two months and who have performed the monitoring for the same months of experience; the interviews will be audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim. Two researchers will carry out the manual analysis and interpretation of the collected data independently, identifying themes and sub-themes.

Conclusion: To explore the nurses’ experiences in this field could facilitate the identification of the educational needs, at individual and group level. Despite it is important to consider contextual variables, the findings of this study could contribute to develop evidence supporting advanced and specialized nursing care in the haematological setting.

Keywords: hematology, nursing, CAR-T therapy, phenomenological, qualitative.

INTRODUCTION

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy is the latest immunotherapy approach for the treatment of certain resistant or relapsing haematological cancers [1], including: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. However, despite being designed to act selectively in eliciting a targeted immune response against neoplastic cells, anti-CD19 CAR-T cell therapy is not free of risks and even serious side effects. The most frequent toxicities are Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS), reported in 57% to 93% of patients who underwent CAR-T [2], and Immune Effector Cells Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS), which occurs in 20% to 70 % of patients [3]. Nevertheless, while they are often manageable and reversible, they can prove fatal, requiring close patient monitoring, early recognition of toxicities, and prompt intervention to reduce morbidity and mortality [3].

To achieve this, patients are closely monitored by nurses after infusions following specific protocols and procedures adopted in the operating units. More specifically, monitoring by nurses includes the assessment of vital parameters as well as typical signs and symptoms of Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) and neurological toxicity (ICANS) [4]. Specifically, to facilitate the identification of early manifestations of neurotoxicity, close monitoring using validated nursing instruments [5] is necessary, including the handwriting test and the quantification of the “ICE - Immune Effector Cell-associated Encephalopathy score”. The latter enables the mental status of patients to be assessed by identifying four ICANS grades (numbered 1 to 4) according to the presence or absence of consciousness impairment, seizures, motor alterations and symptoms of high intracranial pressure [6].

Thus, monitoring enables the nurse to conduct a targeted assessment of the patient's condition in the post-infusion phase, which is decisive for a timely approach to CAR-T toxicities by activating the entire multidisciplinary team. Said approach effectively relies on the meticulous execution of the objective examination, where a high patient assessment frequency [7] enables the practitioner to perceive even the most subtle changes in the patient's psycho-physical condition.

A recent study showed that for patients undergoing CAR-T cell therapy and experiencing significant side effects, continuous monitoring by nurses provides them with a sense of security, and they particularly appreciate the time nurses devote (in addition to monitoring activity) to engaging in dialogue and expressing an interest in their state of health [8]. Therefore, it is essential to acquire deeper insights into the challenges nurses face during the complication monitoring phase, considering that patients may sense such difficulties, which may, consequently, affect the caring relationship established during this crucial assistance.

As a fundamental aspect of nursing practice, the nurse-patient relationship is part of a broader context in which nurses use their senses, knowledge, and experience to exercise professional judgment and discernment when providing care in specific situations [9]. As such, a thorough examination of patients' care experience and the related outcomes must also be conducted with due consideration for the experiences narrated by the haematology nursing staff, since the practice of nursing care necessarily implies a shared experience of the relevant dynamics [10,11].

However, the topic of nursing care in the management of patients undergoing CAR-T cell therapy is a relatively new area of investigation, so few studies have been conducted in the field of nursing. The limited literature has only investigated the experience of patients undergoing CAR-T therapy and/or their caregivers without delving into the experience itself and the meaning attributed to this experience by those who care for patients and/or interact with and support caregivers [12-14]. Moreover, only one study, conducted in China, investigated the experience of a group of oncology nurses in managing this specific subpopulation of patients but was focused on nursing competence [15]. This study did not examine the nurse's key role during the toxicity monitoring phase in-depth, and the main focus was on aspects related to nursing skills rather than the significance of the experience.

To date, to the best of our knowledge, no study has explored nurses' experiences in the monitoring and care of this specific category of haematological patients, even though the aforementioned scientific literature frequently emphasises the importance of nursing care at all stages of the clinical care process and particularly during the post-infusion phase.

Study aim

The purpose of this study is to explore the experience of nurses caring for haematology patients during the monitoring of the main toxicities associated with CAR-T therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

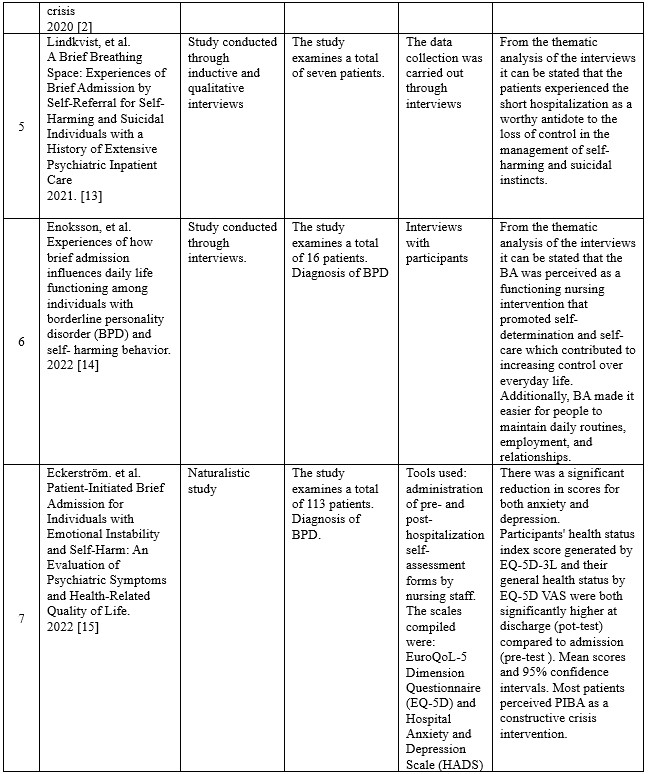

A hermeneutical phenomenological study will be conducted according to Cohen’s method [16]. A summary of the planned operating times for the study is shown in Table 1.

| Study phases | Activities | Estimated duration (time) | Follow-up |

| Definition and planning | Review and analysis of the literature, research question | 1 month (September) | Focus: researchers; stakeholders. |

| Development of the research design, context analysis, selection of potential data acquisition centres | 2 months (October–November) | ||

| Drawing up of draft protocol | 2 months (December–January) | ||

| Review and finalisation of the protocol. | 2 months (February–March) | ||

| Authorisations by the participating centres.

Request for an opinion form the Ethics Committee (EC) |

2 months and 15 days (April–June) | ||

| “Bracketing” process and exchanges between researchers | 15 days (June) | ||

| 2. Recruitment of participants | Recruitment of data acquisition centre and participants | 15 days (July) | Focus: participants |

| Finalisation of the sampling plan | |||

| Informed consent | |||

| Data collection | Pre-test data collection tool (pilot interviews) and finalisation of interview questions | 15 days (July) | |

| Conduct of interviews and return of transcripts | 1 month (August–September) | ||

| Data analysis | Data preparation: transcription, reading of interviews (units of meaning)# | 1 month (September–October) | Focus: texts (transcribed interviews) |

| Data codification and reduction process | |||

| Thematic analysis | |||

| Writing and editing | |||

| Discussion and sharing of emerging themes (provisional) | 15 days (October) | Focus: researchers, participants | |

| Final report | Drafting of the final report, manuscript. | 1 month (November) | Focus: scientific community, stakeholders |

Table 1. Envisaged timeline for the study (2023–2024).

The phenomenological approach is based on the understanding of questions of meaning and the actual experiences of informants [16] by combining the methodological properties of descriptive (Husserlian) and interpretative (Gadmerian) phenomenology. The former descriptive scope aims to describe the experiences of individual members of the cohort under study after a preliminary phase in which the researchers set aside prejudices and preconceptions about the phenomenon under investigation (“bracketing”). This is crucial to reduce the influence of such prejudices and preconceptions on the subsequent phase, in which the themes and data emerging from the interviews are respectively extrapolated and analysed. The interpretative intent, on the other hand, examines and interprets the reported experiences in depth [17]. Therefore, since this methodological approach focuses on understanding questions of meaning and the real-life experiences of the respondents [16], it is particularly suited to nursing-related research and topics seldom explored in the literature. It is also instrumental in the broader context of a working organisation for identifying perceived needs and the solutions that can best address them [16].

Participants and study context

The participating cohort will be recruited from haematology operating units in Italy, identified at the national level among the accredited haematology and onco-haematology centres of advanced specialisation for the treatment of leukaemias and lymphomas, compliant with specific requirements and authorisations for cell therapies as prescribed by AIFA, the Italian Medicines Agency.

Intentional (“propositional”) sampling will be carried out within each data collection centre according to a homogeneity criterion [18,19] to investigate differences and variations within a relatively homogeneous sample [18, 20] in relation to experience in handling the monitoring cards of patients subject to complications associated with CAR-T therapy. This sampling will enable the researchers to deliberately select a cohort of nurses who possess specific expertise and experience in the management of complication monitoring based on a set of pre-established criteria (inclusion and exclusion criteria); this is of fundamental importance in order to obtain a sample capable of providing meaningful, subject-specific information as well as credible and reliable explanations of the phenomenon under study, irrespective of the cohort size [21].

Sampling will continue until data saturation is reached, understood as a process of conducting interviews sequentially until the concepts expressed by the respondents are repeated several times without introducing new concepts or themes [22]. The unitary element of analysis will coincide with the experience under study; therefore, considering that a single respondent can generate many concepts, large samples in numerical terms are not necessarily useful for generating a comprehensive dataset with respect to the purpose of the study and the phenomenon of interest [23]. Indeed, in a qualitative dataset, most new information is generated early in the process and generally follows an asymptotic curve whereby new information declines after a small number of interviews or data analyses [24]. In particular, with regard to studies marked by a high level of population homogeneity, the literature indicates that a sample of six interviews is sufficient to foster the development of meaningful themes and useful interpretations related to the phenomenon under study [25]. Therefore, in accordance with the above and considering that the scope of phenomenology is to explore the common features of real-life experiences gleaned from data provided by only a few individuals who have experienced a particular phenomenon as subjects capable of providing detailed and in-depth information [23], in accordance with claims stated in the literature regarding sample sizes for phenomenological studies, which generally vary from 5 to 25 respondents [26], a sample cohort of 6 to 12 nurses is deemed acceptable for this study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Subject to voluntarily agreeing to participate in the study by signing the informed consent, the study will include all nurses who provide direct patient care at the data collection centres and who have passed the probationary period within the organisation for the inclusion of newly recruited or newly assigned nurses in the operating unit. The selected nurses will have had appreciable experience (for a minimum of two months) in managing patients undergoing CAR-T therapy and must be practised in the use of assessment tools (at least on one occasion) during the same months of experience.

Nurses who provide day hospital care at the operating unit and those in exclusively organisational roles will be excluded from the study.

Data collection tools and study procedures

Interview

For data collection, we developed a draft semi-structured interview outline with open-ended questions that will allow participants to express themselves freely [16]. The interview outline was drawn up considering previous similar studies carried out in the haematology field [12-15] and following discussion within the research group and discussion with expert haematology clinicians working in an accredited Italian haematology and oncohaematology centre with high specialisation in the treatment of leukaemias and lymphomas, meeting specific requirements and authorisations for cell therapies.

The envisaged main questions are as follows: “Please could you tell us about your experience with monitoring CAR-T therapy-induced toxicities for patients in the Haematology Unit?; “How would you describe your experience using CRS and neurological toxicity monitoring tools such as the ICE score and the handwriting test?”; “Regarding your experience, what were the positive and negative aspects? Can you please provide some examples?”. If further investigation of the emerging themes is required, the researcher will add specific questions to the interview to clarify the contents expressed. Finally, the interview will conclude by asking participants if they need to add anything else or report anything specific to what has already been said. This will be solicited by the following question: “Do you have any further comments or suggestions?”; in the event of a negative response, the interview will be considered completed.

In addition, demographic data will be collected from participants relating to age, gender, level of education, marital status, years of work as a nurse, years of work as a nurse in the current haematology unit, previous clinical experience (work areas/clinical specialities in which you have served as a nurse).

Once the necessary ethical authorisations for study commencement have been obtained, a limited number of pilot interviews (at least two) will be conducted to test the draft interview outline and possibly fine-tune it before proceeding with the study.

Data collection

In keeping with the method proposed by Cohen and co-authors [16], before conducting the interviews, all researchers will undertake a process aimed at suspending, i.e. bracketing their personal expectation bias, assumptions, and preconceptions, if any, regarding the phenomenon being studied. According to the proposed method, this approach is crucial as it reduces the likelihood of the researcher's judgements influencing the extrapolation of themes from the interviews [16].

Each interview will be conducted face-to-face, individually, by a researcher with professional experience in the field of haematology, but who is not part of the team working in the data collection centre. In addition, interviews will be conducted by prior agreement with the individual participant in a location that ensures participants feel comfortable, facilitating spontaneous and natural responses [16].

Subject to written informed consent, each interview will be recorded using protected digital tools that are not accessible except to researchers so that they can subsequently be transcribed verbatim for data analysis purposes. Subsequently, the transcripts will be returned to the interviewees for comments or clarification. Considering the impossibility of establishing a predetermined interview duration, given the purpose of the study and the complexity of the phenomenon to be examined, a time of between 40 and 70 minutes is envisaged for each interview.

Data analysis

Two researchers will independently analyse the data extracted from the interviews using a manual approach [27,28]. In accordance with the method of Cohen and co-authors [16], the data analysis will comprise the following principal phases: (I) The Data Preparation Phase, in which the interviews, previously recorded, will be transcribed verbatim and transferred to digital media; in this phase, the units of analysis (words, phrases or themes) will be selected, and a repeated and in-depth reading of the transcripts will be carried out, through the process of immersion in the data [29] to become familiar with the transcripts and highlight the essential features within each interview [30,31] while simultaneously carrying out an initial interpretation of the contents that will guide the codification of the data in the subsequent analysis phases [16]. (II) the Data Codification and Reduction Process: in this phase, the researchers will reorganise the contents of the interviews, grouping content pertaining to the same subject, eliminating any digressions that stray from the phenomenon under study and simplifying the respondents' spoken language without actually modifying the content expressed; a “line by line” analysis of what the participants reported will be carried out to provide “a label of meaning” to each part of the text [16], starting the reduction process while maintaining the overall essence of the contents expressed [16]. (III) Thematic Analysis: the purpose of the thematic analysis is to systematically describe and interpret the meaning of the qualitative data generated by the interviews, generating themes that will be finally analysed and presented [32]. At this stage, once an overall interpretation of the contents has been obtained, sentences in the text will be underlined by writing “headings” in the margin of the text that will represent the provisional names and/or themes assigned to the most salient content aspects [16,33-36]. To this end, colours may be used, or specific text segments may be highlighted to indicate potential interpretative patterns instrumental to identifying data segments; similarly labelled interview passages will then be grouped and appropriately reorganised [16]. In this way, as the main headings are identified, the extracted data will be collected and grouped manually within each codification, generating an initially unrestricted list of categories [36]. (IV) The Writing and Editing Process [35]: a reflexive writing and rewriting process will initially identify themes that will be followed by an in-depth examination and comparative analysis of the same within a broader framework to validate the overall meaning derived from the contents of the interviews [16]. The lists of categories will then be grouped into higher-order headings of broader scope capable of describing and augmenting the understanding of the phenomenon, thereby generating new knowledge [36]. The category reduction process will involve pooling similar or related observations and comparing data from within the same category with data from other categories [36]. Finally, the abstraction process will make it possible to formulate a general description of the phenomenon under study by formulating specific categories (general and subcategories) that will be named using words that reference their content [29]. A deep probing of the meaning of the interview content will lead to an overall understanding of the respondents’ real-life experiences as expressed within the emergent themes. This understanding will be supported by recourse to margin notes as part of the hermeneutic process underlying the transformation of the text fields into a coherent narrative [16,37]. (V) Following thematic analysis, the researchers will discuss the provisional emergent themes with the other members of the research team, including qualitative research and haematology nursing experts. Subsequently, the provisional themes will be returned to the participants to verify that the researchers had correctly interpreted their submissions, and only then will they be confirmed.

Methodological rigour

To minimise social desirability bias, the interviews will be conducted by a researcher who has no previous involvement with the study centre in a professional capacity. The researchers tasked with analysing the data will also have previous oncological work experience, albeit in different settings other than the data collection centre; this will underpin the credibility of the research process. The practice of “bracketing” will promote critical thinking among researchers to ensure methodological rigour and avoid the contamination of individual judgement during data analysis [16]. The practice of “bracketing” will promote critical thinking among researchers, ensuring methodological rigour and avoiding the contamination of individual judgement during data analysis [16]. Furthermore, to reinforce the collaborative relationship between participants and researchers and confirm the accuracy of outcomes, respondents will be asked to provide feedback on the (provisional) themes identified (member-checking of participants); they will also be offered the opportunity to add details or clarifications regarding their experience, if necessary [38].

Ethical considerations and protection of data confidentiality

The study was submitted to an independent Ethics Committee, which expressed a favourable opinion on the conduct of the study (Project identification code 1697/CEL – CARTINF Study; approval number 389|13/06/2024).

Nurses' involvement in the survey will be voluntarily, and the semi-structured interviews will be preceded by asking study participants for written consent to their participation, recording of the interviews, and processing of related data. They will also receive all information about the study's purpose, how data is collected and managed, and its confidentiality.

Anonymity will be guaranteed as prescribed by prevailing legislation on the processing of personal data and respect for privacy (Italian Laws nos. 675 & 676 of 31 December 1996, Official Journal of 08/01/1997, Article 7 of Italian Legislative Decree no. 196 of 30 June 2003 and European Privacy Regulation EU 2016/679, General Data Protection Regulation – GDPR). Relevant data will be strictly used for the purposes of the study.

Presentation of results

The results of the study will be presented in narrative form, reporting excerpts from interviews in support of the identified themes and sub-themes. Furthermore, graphic aids in the form of charts and tables will be included to enhance visualisation of the interview outcomes and related analyses (e.g. with respect to the originally codified themes) in terms of response frequencies and percentages [32]. In particular, tables may be used to express thematic outcomes quantitatively (e.g. organisation of the various themes according to the number of codes they contain), the intent being to facilitate and not replace the presentation of the interview extracts in narrative form.

DISCUSSION